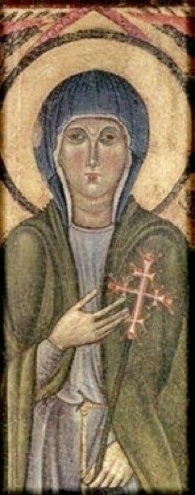

Clare of Assisi

Almost 800 years ago, on Palm Sunday evening in the year 1212, a young girl from an aristocratic Umbrian family dramatically fled her family home under cover of darkness to join Francis of Assisi and his brothers. In the valley below the town of Assisi she met them in the tiny church of St. Mary of the Angels that Francis had repaired after his conversion. She was ritually welcomed into this family of brothers, and promised herself to God that night. Her hair was cut and she was clothed in the simple tunic that identified her as part of the group, the minores, the “little ones”. Clare di Offreduccio, later known simply as Clare of Assisi, risked everything that night to respond to the compelling call to seek God, to leave everything behind – status, security, family name, home, wealth – for the one thing necessary.

The early thirteenth century was a time of political and civil instability in central Italy. Towns warred against each other and tensions between the rising merchant class and the aristocratic classes resulted in open and destructive conflict. It was also a time when the traditional structures of religious life were being challenged. The primary expression of religious life was monasticism. Typically, a woman entering a monastic community brought with her a significant dowry (land, cash, and/or goods). Moreover, wealthy relatives or supportive clerics would provide the monastery, over time, additional bequests of property, money, and other assets. In most cultures, land and wealth provide access to the powerful and to the institutions of power. Medieval monasteries were no exception.

As children of their generation, Francis and Clare, and those who joined them, rejected the prevailing institutional models – political, economic, cultural and religious – that ordered and controlled their world. In their own ways, each not only renewed religious life, but also brought something completely new to religious life, the prophetic vision to imagine that God was doing a new thing among them. They sought a manner of living that was relational, a search for God and the Spirit that was honest, simple, poor, rigorous, gentle, sometimes extreme, joyful, a way of peace based in mutuality and respect that emanated from their primary spiritual experience of Jesus as Incarnate. This was life in the Trinity. For Francis and for Clare, the Christ-life was an embodied life and the only way into the Christ-life, the gospel life, was through poverty.

From the beginning of Clare’s foundation until the death of Francis in 1226, such a singularity of spirit remained between Francis and Clare that later, Francis’ early biographer, Thomas of Celano was to write (while Clare was still alive),

As long as he [Francis] lived

he always carried this out with eagerness,

and when he was close to death

he emphatically commanded that it should be always so,

saying that one and the same spirit

had led the brothers and the poor ladies

out of the world. (2 Cel 204)

Clare, and the sisters who joined her, lived at San Damiano for the next forty-seven years. During those years they succeeded in giving feminine expression to the Franciscan charism. They desired to live the gospel through a life of poverty (sine proprio, without anything of their own), a life of contemplation, a life attentive to the Spirit of the Lord and the Spirit’s holy manner of working.

Choosing this form of life, however, was not without its difficulties. The primary challenges to articulating and living a Franciscan life for women came from a succession of Popes: Honorius III, Gregory IX, and Innocent IV. Because of the proliferation of groups of women throughout the Italian peninsula seeking to live a religious life without papal approbation, these popes were determined to regularize women’s religious life through juridical norms, imposing on these groups severe and exacting rules that ignored specific charisms distinctive to each group, and that regulated even the most minute aspects of life. Nevertheless, Clare and her sisters persisted in living the gospel life as they understood it, and in August 1253, on her deathbed, Clare finally received pontifical approval for the rule she and the sisters had written for their way of life. The Rule (The Form of Life of Clare of Assisi) was the first written by a woman to receive papal approval and is used today by many Poor Clare communities throughout the world.

Clare had joined the brothers, but neither Francis (and the brothers) nor the Church were ready for a woman to live the unrestricted, unprotected, public life led by men, particularly the itinerant life that characterized the nascent Franciscan movement. Rather quickly Clare was dispatched to a Benedictine monastery for her protection, and a short time later Francis settled her and the women who accompanied her at San Damiano, another of the churches he had repaired. Afterwards, Francis wrote a short vita forma (form/way of life) for them that indicated they had joined the brothers,

Because by divine inspiration

you have made yourselves

daughters and servants of the

most High King, the heavenly Father,

and have taken the Holy Spirit

as your spouse, choosing to live

according to the perfection of the

Holy Gospel,

I resolve and promise for myself

and for my brothers

always to have that same loving care

and special solicitude for you

as [I have] for them. (RCl 6:3-4)

Ortolana Ofreduccio, a noble woman from the Italian town of Assisi, pregnant

with her first child, went to pray before a cross in 1193, asking God for the

safety of her child and herself during the delivery. While at prayer she heard

a voice and received a prophecy about the child in her womb:

“Do not be afraid, Woman, for you will give birth in safety to a light

which will give light more clearly than light itself.”

When the child was born, Ortolana named her Chiara, or Clare,

“the clear one”, “light”, “brightness.”

Never let the thought of God leave your mind. - St. Clare